摩西

摩西(希伯來文:מֹשֶׁה,羅馬拼音:現代 Moshe、Tiberian Mōšeh;古希臘文:Mωϋσῆς;阿拉伯文:موسىٰ,羅馬拼音:Mūsa;英文:Moses),天主教叫梅瑟,景教叫牟世法王,係希伯來聖經之中,一位宗敎領袖、法律制訂人以及先知。傳統上,認為五經係佢寫嘅。希伯來文中,又叫佢做 「我哋嘅先生(拉比)摩西」(希伯來文:מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ,羅馬拼音:Moshe Rabbenu)。佢係猶太敎中,係極為重要嘅先知。基督敎同回敎等宗敎之中,都認為佢係好重要嘅先知。

根據《出埃及記》,摩西響佢族人大增嘅時候出世,埃及王驚佢哋會幫敵人手,所以就要殺晒所有族人啱啱出世嘅男仔。而摩西就響呢個時候出世,之而過去咗埃及王室屋企,避過呢劫。佢最後帶領喺埃及過住奴隸生活嘅以色列人離開埃及,到達上帝所預備嘅流奶與蜜之地—迦南地。

大多數學者認為聖經中嘅摩西係一個傳奇人物,但仍然保留摩西或者類似摩西嘅人物喺公元前13世紀存在嘅可能性。[1][2][3][4][5] 拉比猶太教計算出摩西嘅壽命係公元前1391年至1271年;[6] 杰羅姆建議係公元前1592年,[7]而詹姆斯·厄舍建議佢出生於公元前1571年。[8][註 1] 埃及名字「摩西」喺古埃及文學中有提及。[11]喺猶太歷史學家約瑟夫嘅著作中,引用咗古埃及歷史學家馬内托嘅記載,講述一個叫奧薩爾瑟夫嘅叛逆古埃及祭司,佢改名做摩西,帶領一場成功嘅政變反對當時嘅法老,之後統治埃及幾年,直到法老重新掌權並驅逐咗奧薩爾瑟夫同佢嘅支持者。[12][13][14]

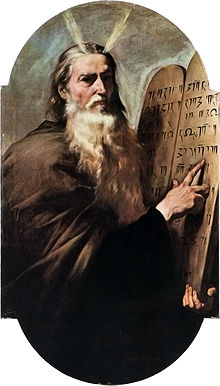

摩西經常喺基督教藝術同文學中被描繪,例如米開朗基羅嘅《摩西》同埋喺好幾棟美國政府大樓嘅作品。喺中世紀同文藝復興時期,佢經常被描繪成有細角,呢個係由於武加大譯本聖經嘅拉丁文翻譯錯誤引起嘅,儘管有時候呢個可能反映基督徒嘅矛盾心態或者有明顯嘅反猶太主義含義。

名字嘅詞源

編輯埃及語詞根msy(「……嘅仔」)或者mose被認為可能係個詞源,[15]可以話係省略咗神嘅名字嘅神名縮寫。後綴mose喺埃及法老嘅名字中出現過,例如圖特摩斯(「托特所生」)同拉摩斯(「拉所生」)。[16] 拉美西斯嘅其中一個埃及名字係Ra-mesesu mari-Amon,意思係「拉所生,阿蒙所愛」(佢仲叫做Usermaatre Setepenre,意思係「光明同和諧嘅守護者,光明中嘅強者,拉嘅選民」)。語言學家亞伯拉罕·耶胡達根據塔納赫畀出嘅拼寫,認為佢結合咗「水」或者「種子」同「池塘,水面」,因此得出「尼羅河之子」嘅意思(mw-š)。[17]

聖經記載摩西出生嘅故事為佢提供咗一個民間詞源學嚟解釋佢名字嘅表面意思。[16][18] 據講係法老嘅女兒畀佢呢個名:「佢成為咗佢個仔。佢叫佢摩西 [מֹשֶׁה,Mōše],話:『我將佢從水中拉出嚟 [מְשִׁיתִֽהוּ,mǝšīṯīhū]。』」[19][20] 呢個解釋將佢同閃米特語系詞根משׁה,m-š-h聯繫起嚟,意思係「拉出嚟」。[20][21] 11世紀嘅托沙福特學者以撒·本·亞設·哈利維指出,公主畀佢嘅名字係主動分詞「拉出者」(מֹשֶׁה,mōše),而唔係被動分詞「被拉出者」(נִמְשֶׁה,nīmše),實際上預言摩西會將其他人拉出(埃及);呢個解釋已經被一啲學者接受。[22][23]

聖經故事中嘅希伯來語詞源可能反映咗一種抹去摩西埃及出身痕跡嘅嘗試。[23] 佢名字嘅埃及特徵已經被古代猶太作家如斐洛同約瑟夫認定。[23] 斐洛將摩西嘅名字(古希臘文:Μωϋσῆς,羅馬拼音:Mōysēs,意思係 「Mōusês」)同埃及(科普特語)嘅「水」字(môu,μῶυ)聯繫起嚟,呢個係講緊佢喺尼羅河畔被發現同聖經嘅民間詞源學。[註 2] 約瑟夫喺佢嘅《猶太古史》中聲稱,第二個元素-esês嘅意思係「被拯救嘅人」。一個埃及公主(根據《出埃及記》嘅聖經記載,係佢畀摩西呢個名)點解會識希伯來語呢個問題令中世紀嘅猶太評論家如亞伯拉罕·伊本·以斯拉同希西家·本·馬諾阿都感到困惑。希西家建議佢要麼皈依咗猶太教,要麼從約基別(摩西嘅母親)嗰度得到咗提示。[24][25][26] 喺《出埃及記》中畀摩西改名嘅埃及公主冇畀名。不過,約瑟夫知道佢叫做塞穆提斯(識別為塞穆特),[20]而一啲猶太傳統嘗試將佢同《歷代志上》4:17中一個叫做比提雅嘅「法老嘅女兒」聯繫起嚟,[27]但其他人指出呢個可能性唔大,因為冇文本跡象顯示呢個法老嘅女兒就係畀摩西改名嗰個。[27]

伊本·以斯拉對摩西個名嘅由來畀咗兩個可能性:佢相信要麼係埃及名字嘅翻譯而唔係音譯,要麼法老嘅女兒識講希伯來語。[28][29]

註

編輯疏仕

編輯- ↑ Nigosian, S.A. (1993). "Moses as They Saw Him". Vetus Testamentum. 43 (3): 339–350. doi:10.1163/156853393X00160. ISSN 0042-4935.

Three views, based on source analysis or historical-critical method, seem to prevail among biblical scholars. First, a number of scholars, such as Meyer and Holscher, aim to deprive Moses all the prerogatives attributed to him by denying anything historical value about his person or the role he played in Israelite religion. Second, other scholars,.... diametrically oppose the first view and strive to anchor Moses the decisive role he played in Israelite religion in a firm setting. And third, those who take the middle position... delineate the solidly historical identification of Moses from the superstructure of later legendary accretions….Needless to say, these issues are hotly debated unresolved matters among scholars. Thus, the attempt to separate the historical from unhistorical elements in the Torah has yielded few, if any, positive results regarding the figure of Moses or the role he played on Israelite religion. No wonder J. Van Seters concluded that "the quest for the historical Moses is a futile exercise. He now belongs only to legend

- ↑ Dever, William G. (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3.

A Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in southern Transjordan in the mid-late 13th century s.c., where many scholars think the biblical traditions concerning the god Yahweh arose.

- ↑ Beegle, Dewey (5 July 2023). "Moses". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Moses". Oxford Biblical Studies Online.

- ↑ Miller II, Robert D. (25 November 2013). Illuminating Moses: A History of Reception from Exodus to the Renaissance. BRILL. pp. 21, 24. ISBN 978-90-04-25854-9.

Van Seters concluded, 'The quest for the historical Moses is a futile exercise. He now belongs only to legend.' ... "None of this means that there is not a historical Moses and that the tales do not include historical information. But in the Pentateuch, history has become memorial. Memorial revises history, reifies memory, and makes myth out of history.

- ↑ Seder Olam RabbahTemplate:Full citation needed

- ↑ Jerome嘅Chronicon(4世紀)畀出摩西嘅出生年份係公元前1592年

- ↑ 17世紀嘅Ussher chronology計算出公元前1571年(《世界年鑑》,1658年第164段)

- ↑ 聖奧古斯丁。《上帝之城。第十八卷。第8章 - 摩西出生時邊個係國王,喺當時開始崇拜咩神》

- ↑ Hoeh, Herman L (1967), Compendium of World History (dissertation),第1卷, The Faculty of the Ambassador College, Graduate School of Theology, 1962.

- ↑ "Let's Hear It From The Pharaohs: The Egyptian Story of Moses". Museum of the Jewish People. April 7, 2020. 原著喺2024年5月25號歸檔. 喺June 8, 2024搵到.

- ↑ Gruen, Erich S. (1998). "The Use and Abuse of the Exodus Story". Jewish History. Springer. 12 (1): 93–122. doi:10.1007/BF02335457. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101326. 喺June 8, 2024搵到.

- ↑ Feldman, Louis H. (1998). "Responses: Did Jews Reshape the Tale of the Exodus?". Jewish History. Springer. 12 (1): 123–127. doi:10.1007/BF02335458. ISSN 0334-701X. JSTOR 20101327. 喺June 8, 2024搵到.

- ↑ "MOSES IS CURED OF LEPROSY". Jewish Bible Quarterly. September 12, 2016. 喺June 8, 2024搵到.

- ↑ Davies 2020, p. 181.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hays, Christopher B. (2014). Hidden Riches: A Sourcebook for the Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near East. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-664-23701-1.

- ↑ Ulmer, Rivka. 2009. Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash. de Gruyter. p. 269.

- ↑ Naomi E. Pasachoff, Robert J. Littman (2005), A Concise History of the Jewish People, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 5.

- ↑ Exodus 2:10

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Maciá, Lorena Miralles. 2014. "Judaizing a Gentile Biblical Character through Fictive Biographical Reports: The Case of Bityah, Pharaoh's Daughter, Moses' Mother, according to Rabbinic Interpretations". pp. 145–175 in C. Cordoni and G. Langer (eds.), Narratology, Hermeneutics, and Midrash: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Narratives from Late Antiquity through to Modern Times. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ↑ Dozeman 2009, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ "Riva on Torah, Exodus 2:10:1". Sefaria. 喺2021-03-14搵到.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Greifenhagen, Franz V. 2003. Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map: Constructing Biblical Israel's Identity. Bloomsbury. pp. 60ff [62] n.65. [63].

- ↑ Shurpin, Yehuda. Is Moses a Jewish or Egyptian Name?. Chabad.org.

- ↑ Salkin, Jeffrey K. (2008). Righteous Gentiles in the Hebrew Bible: Ancient Role Models for Sacred Relationships. Jewish Lights. pp. 47ff [54].

- ↑ Harris, Maurice D. 2012. Moses: A Stranger Among Us. Wipf and Stock. pp. 22–24.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Scolnic, Benjamin Edidin. 2005. If the Egyptians Drowned in the Red Sea where are Pharaoh's Chariots?: Exploring the Historical Dimension of the Bible. University Press of America. p. 82.

- ↑ "Did Pharaoh's Daughter Name Moses? In Hebrew?". TheTorah.com. 喺2022-04-18搵到.

- ↑ Danzinger, Y. Eliezer (2008-01-20). "What Was Moshe's Real Name?". Chabad.org. 喺5 May 2022搵到.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (2003), pp. 296–97: "His name is widely held to be Egyptian, and its form is too often misinterpreted by biblical scholars. It is frequently equated with the Egyptian word 'ms' (Mose) meaning 'child', and stated to be an abbreviation of a name compounded with that of a deity whose name has been omitted. And indeed we have many Egyptians called Amen-mose, Ptah-mose, Ra-mose, Hor-mose, and so on. But this explanation is wrong. We also have very many Egyptians who were actually called just 'Mose', without omission of any particular deity. Most famous because of his family's long lawsuit in the middle-class scribe Mose (of the temple of Ptah at Memphis), under Ramesses II; but he had many homonyms. So, the omission-of-deity explanation is to be dismissed as wrong ... There is worse. The name of Moses is most likely not Egyptian in the first place! The sibilants do not match as they should, and this cannot be explained away. Overwhelmingly, Egyptian 's' appears as 's' (samekh) in Hebrew and West Semitic, while Hebrew and West Semitic 's' (samekh) appears as 'tj' in Egyptian. Conversely, Egyptian 'sh' = Hebrew 'sh', and vice versa. It is better to admit that the child was named (Exod 2:10b) by his own mother, in a form originally vocalized 'Mashu', 'one drawn out' (which became 'Moshe', 'he who draws out', i.e., his people from slavery, when he led them forth). In fourteenth/thirteenth-century Egypt, 'Mose' was actually pronounced 'Masu', and so it is perfectly possible that a young Hebrew Mashu was nicknamed Masu by his Egyptian companions; but this is a verbal pun, not a borrowing either way."