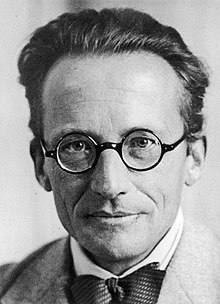

埃爾溫·薛定諤

埃爾溫·薛定諤(粵音:sit3 ding6 ngok6;德文:Erwin Schrödinger,德文讀音: [ˈɛʁvɪn ˈʃʀødɪŋɐʁ];1887年8月12號—1961年1月4號)係奧地利量子力學物理學家,量子力學奠基人,1933年憑住提出薛定諤方程式(Schrödinger equation)同英國物理學家狄勒(Paul Dirac)一齊攞咗諾貝爾物理學獎[1]。

| 埃爾溫·薛定諤 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 姓名原文 | Erwin Schrödinger |

| 出生日 | 1887年8月12號 |

| 出生地 | 維也納 |

| 本名 | Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger |

| 死亡日 | 1961年1月4號 |

| 死亡地 | 維也納 |

| 死因 | 肺癆 |

| 國籍 | Cisleithania、德國、納粹德國 |

| 識嘅語言 | 德文 |

| 信奉 | 無神論 |

| 母校 | 牛津大學、維也納大學、Akademisches Gymnasium |

| 職業 | 物理學家、理論物理學家、學者、教授、非虛構文學作家、數學家 |

| 僱主 | 維也納大學、University of Stuttgart、University of Jena、蘇黎世大學、University of Graz、Frederick William University Berlin、University of Wrocław、柏林洪堡大學、牛津大學、根特大學、Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies |

| 名作 | 薛定諤方程式、薛定諤貓 |

| 配偶 | Annemarie Schrödinger |

| 仔女 | Ruth Braunizer |

| 阿爸 | Rudolf Schrödinger |

[改維基數據] | |

佢寫咗好多關於唔同範疇嘅物理學嘅著作:統計力學同熱力學、電介質物理、色彩理論、電動力學、廣義相對論同宇宙學,仲試過幾次建立統一場論。喺佢本書《生命係咩?》入面,薛定諤由物理學嘅角度探討咗遺傳學嘅問題,研究生命呢個現象。佢仲好關注科學嘅哲學層面、古代同東方嘅哲學概念、倫理同宗教。[2]佢仲寫過關於哲學同理論生物學嘅文章。喺大眾文化入面,佢最出名嘅就係佢嘅「薛定諤貓」思想實驗。[3][4]

薛定諤一生大部分時間都喺唔同大學做學者,同狄勒一齊喺1933年因為佢哋喺量子力學方面嘅工作而獲得諾貝爾物理學獎,同年佢因為反對納粹主義而離開德國。喺佢嘅私生活中,佢同時同佢嘅妻子同情婦一齊住,可能因為咁而導致佢要離開牛津大學嘅職位。之後,直到1938年,佢喺奧地利格拉茨大學教書,到1938年德奧合併之後走佬,最後喺愛爾蘭嘅都柏林度,搵到長期嘅安排。佢喺嗰度一直做到1955年退休,期間曾經同過幾個未成年人發生過性關係。

生平

編輯早年

編輯薛定諤喺1887年8月12日出世喺奧地利首都維也納,佢爸爸 Rudolf Schrödinger 係植物學家[5][6],佢阿媽 Georgine Emilia Brenda Schrödinger 係化學教授 Alexander Bauer 嘅女[7]。薛定諤係佢哋嘅獨生仔。

佢阿媽係半個奧地利人半個英國人;佢爸爸係天主教徒,而佢阿媽係路德宗教徒。佢自己係個無神論者。[8]不過,佢對東方宗教同泛神論好有興趣,仲會喺佢嘅作品入面用宗教符號。[9]佢仲相信佢嘅科學工作係從智力上接近神性嘅一種方式。[10]

佢仲可以喺學校以外學到英文,因為佢外婆係英國人。[11]1906年到1910年之間(佢拎到博士學位嗰年),薛定諤喺維也納大學跟住物理學家 Franz S. Exner(1849-1926)同 Friedrich Hasenöhrl(1874-1915)讀書。佢喺維也納跟住Hasenöhrl拎到博士學位。佢仲同Karl Wilhelm Friedrich "Fritz" Kohlrausch一齊做實驗工作。1911年,薛定諤成為咗Exner嘅助手。[6]

中年時期

編輯1914年,薛定諤完成咗講師資格論文(venia legendi)。1914年到1918年之間,佢以奧地利要塞砲兵嘅軍官身份參與戰爭工作(戈里齊亞、杜伊諾、西斯蒂亞納、普羅塞科、維也納)。1920年,佢成為耶拿嘅Max Wien嘅助手,同年9月佢喺斯圖加特獲得咗ausserordentlicher Professor(差唔多等於英國嘅Reader或者美國嘅副教授)嘅職位。1921年,佢喺布勒斯勞(而家嘅波蘭弗羅茨瓦夫)成為咗ordentlicher Professor(即係正教授)。[6]

1921年,佢搬去咗蘇黎世大學。1927年,佢喺柏林嘅腓特烈·威廉大學接替咗馬克斯·普朗克嘅位置。1933年,薛定諤決定離開德國,因為佢強烈反對納粹嘅反猶太主義。佢成為咗牛津大學莫德林學院嘅院士。佢到咗冇幾耐,就同狄勒一齊攞到諾貝爾物理學獎。佢喺牛津嘅職位搞得唔係幾好;佢唔傳統嘅家庭安排,同兩個女人一齊住,冇受到接納。[12]1934年,薛定諤喺普林斯頓大學講課;佢得到咗一份長期職位嘅offer,但係佢冇接受。再一次,佢想同佢老婆同情婦一齊住可能又搞出咗麻煩。[13]佢本來有機會喺愛丁堡大學搵到份工,但係簽證拖延,最後佢喺1936年接受咗奧地利格拉茨大學嘅職位。佢仲接受咗印度阿拉哈巴德大學物理系主任嘅offer。[14]

喺呢啲任期問題中間,1935年,喺同愛因斯坦大量通信之後,佢提出咗而家叫做「薛定諤貓」嘅思想實驗。[15]

晚年時期

編輯1938年,德奧合併之後,施洛定格因為1933年逃離德國同佢反對納粹主義嘅立場,喺格拉茲開始遇到好多問題。[16] 佢發表咗一份聲明,翻轉佢之前嘅立場。[17] 但佢後來後悔咗,並解釋俾愛因斯坦聽,佢話:「我想保留自由—但要做到呢個,就要靠巨大嘅虛偽。」[17] 但係,呢樣嘢無令新政權完全滿意,格拉茲大學以政治上嘅不可靠性為由,辭退咗佢。佢受到騷擾,仲被指示唔好離開國家。不過,佢同佢老婆都逃去意大利,之後去牛津同根特大學擔任訪問教授。[17][16]

同年,佢收到愛爾蘭總理、數學家艾蒙·戴·華拉嘅個人邀請,叫佢嚟愛爾蘭居住,並同意協助成立都柏林高級研究院。[18] 佢搬咗去都柏林嘅Kincora路,過住簡樸嘅生活。佢喺Clontarf住嗰度同Merrion Square工作嘅地址都立咗紀念牌。[19][20][21] 施洛定格覺得,作為一個奧地利人,佢同愛爾蘭有獨特嘅關係。1940年10月,有位《愛爾蘭報》嘅作家訪問施洛定格,佢講到奧地利人嘅凱爾特血統,佢話:「我相信我哋奧地利人同凱爾特人之間有更深層嘅聯繫。奧地利阿爾卑斯山嗰啲地名據講都係凱爾特來源。」[22] 1940年,佢成為都柏林高級研究院理論物理學校嘅主任,並喺嗰度做咗17年。1948年,佢成為愛爾蘭嘅歸化公民,但亦保留咗佢嘅奧地利國籍。[23] 佢喺唔同嘅課題上面寫咗大概50篇文章,包括佢對古典統一場論嘅探索。[24]

1944年,佢寫咗《生命是甚麼?》,呢本書討論咗負熵同埋一個包含住遺傳密碼嘅複雜分子嘅概念。據詹姆斯·D·沃森嘅回憶錄《DNA,生命嘅秘密》所講,施洛定格嘅書俾咗沃森靈感去研究基因,最後喺1953年發現咗DNA嘅雙螺旋結構。同樣,法蘭西斯·克里克喺佢自傳《What Mad Pursuit》中亦描述咗施洛定格對遺傳訊息點樣儲存喺分子中嘅推測對佢嘅影響。[25] 施洛定格一直留喺都柏林直到1955年退休。

當時,一篇叫《伽利略·伽利萊未出版對話嘅片段》[26]嘅手稿再次喺The King's Hospital寄宿學校出現。[27] 佢當年寫呢篇文章係為咗學校1955年嘅《Blue Coat》版本,來慶祝佢離開都柏林,去到維也納大學擔任物理學講座教授嘅職位。[28]

1956年,佢返返去維也納(擔任「ad personam」講座教授)。喺世界能源會議上進行重要演講嘅時候,佢因為懷疑核能,拒絕咗討論核能,反而進行咗一場哲學演講。呢段時間,施洛定格背離主流嘅量子力學對波粒二象性嘅定義,推動純粹嘅波動觀點,引起咗唔少爭議。[29][30]

肺結核同死亡

編輯睇埋

編輯參考

編輯- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1933". 諾貝爾基金會. 喺2007-11-24搵到.

- ↑ Heitler, W. (1961). "Erwin Schrodinger. 1887–1961". 《英國皇家學會會士傳記錄》. 7: 221–226. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1961.0017. JSTOR 769408.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore. Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge, England, UK: Press Syndicate of Cambridge University Press, 1989. p.194.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., 〈埃爾溫·薛定諤〉, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- ↑ Schrodinger, Rudolf. "The International Plant Names Index". IPNI. 原先內容歸檔喺13 August 2021. 喺13 August 2016搵到.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Physics 1922-1941. Nobel Lectures (美國英文). Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company. 1965. Erwin Schrödinger Biographical. 原先內容歸檔喺7 March 2023. 喺19 February 2023搵到 –透過nobelprize.org.

- ↑ Moore 1994, pp. 13–18.

- ↑ Moore 1994, pp. 289–290 Quote: "In one respect, however, he is not a romantic: he does not idealize the person of the beloved, his highest praise is to consider her his equal. 'When you feel your own equal in the body of a beautiful woman, just as ready to forget the world for you as you for her – oh my good Lord – who can describe what happiness then. You can live it, now and again – you cannot speak of it.' Of course, he does speak of it, and almost always with religious imagery. Yet at this time he also wrote, 'By the way, I never realized that to be nonbelieving, to be an atheist, was a thing to be proud of. It went without saying as it were.' And in another place at about this same time: 'Our creed is indeed a queer creed. You others, Christians (and similar people), consider our ethics much inferior, indeed abominable. There is that little difference. We adhere to ours in practice, you don't.'"

- ↑ Paul Halpern (2015). Einstein's Dice and Schrödinger's Cat. Perseus Books Group. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-465-07571-3. Quote: "In the presentation of a scientific problem, the other player is the good Lord. He has not only set the problem but also has devised the rules of the game--but they are not completely known, half of them are left for you to discover or deduce. I am very astonished that the scientific picture of the real world around me is very deficient. It gives a lot of factual information, puts all our experience in a magnificently consistent order, but is ghastly silent about all that is really near to our heart, that really matters to us. It cannot tell us a word about red and blue, bitter and sweet, physical pain and physical delight; it knows nothing of beautiful and ugly, good or bad, God and eternity. Science sometimes pretends to answer questions in these domains, but the answers are very often so silly that we are not inclined to take them seriously. I shall quite briefly mention here the notorious atheism of science. The theists reproach it for this again and again. Unjustly. A personal God cannot be encountered in a world picture that becomes accessible only at the price that everything personal is excluded from it. We know that whenever God is experienced, it is an experience exactly as real as a direct sense impression, as real as one's own personality. As such He must be missing from the space-time picture. "I do not meet with God in space and time", so says the honest scientific thinker, and for that reason he is reproached by those in whose catechism it is nevertheless stated: "God is a Spirit." Whence came I and whither go I? That is the great unfathomable question, the same for every one of us. Science has no answer for it"

- ↑ Moore 1992, p. 4 Quote: "He rejected traditional religious beliefs (Jewish, Christian, and Islamic) not on the basis of any reasoned argument, nor even with an expression of emotional antipathy, for he loved to use religious expressions and metaphors, but simply by saying that they are naive." ... "He claimed to be an atheist, but he always used religious symbolism and believed his scientific work was an approach to the godhead."

- ↑ Hoffman, D. (1987). Эрвин Шрёдингер. Мир. pp. 13–17.

- ↑ Moore 1992, pp. 278 ff..

- ↑ "Schrödinger, Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander" 互聯網檔案館嘅歸檔,歸檔日期27 April 2011. in Deutsche Biographie

- ↑ "Bombay University Names Refugee Scientist to Faculty". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 20 May 1940. 原先內容歸檔喺27 October 2016. 喺14 August 2016搵到.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Mani L. (2017). "Is Schrödinger's Cat Alive?". Quanta. 6 (1): 75. arXiv:2211.17086. doi:10.12743/quanta.v6i1.68.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Akhlesh Lakhtakia (1996). Models and Modelers of Hydrogen: Thales, Thomson, Rutherford, Bohr, Sommerfeld, Goudsmit, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Dirac, Sallhofer. World Scientific. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-981-02-2302-1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger". MacTutor 數學史檔案. 原先內容歸檔喺4 January 2017. 喺14 August 2016搵到.

- ↑ Daugherty, Brian. "Brief Chronology". Erwin Schrödinger. 原著喺9 March 2012歸檔. 喺10 December 2012搵到.

- ↑ "A quantum leap to Clontarf". The Irish Times. 原先內容歸檔喺27 September 2020. 喺4 June 2020搵到.

- ↑ Fergusson, Maggie (10 November 2016). Treasure Palaces: Great Writers Visit Great Museums. Profile. ISBN 978-1-78283-278-2 –透過Google Books.

- ↑ "Erwin Schrödinger blue plaque". openplaques.org. 原先內容歸檔喺10 June 2020. 喺10 June 2020搵到.

- ↑ Moore 1992, p. 373.

- ↑ Clary, David C. (2022). "Foreign Membership of the Royal Society: Schrödinger and Heisenberg?". Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. 77 (3): 513–536. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2021.0082. S2CID 247599443.

- ↑ "Erwin Schrödinger - Important Scientists – The Physics of the Universe". www.physicsoftheuniverse.com. 原先內容歸檔喺19 February 2023. 喺2023-02-19搵到.

- ↑ Crick, Francis (1988). What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-09137-7.

- ↑ "Fragment from an unpublished dialogue of Galileo" manuscript

- ↑ Ahlstrom, Dick (18 April 2012) 'Quantum humour' beams back after absence 互聯網檔案館嘅歸檔,歸檔日期18 April 2012.. The Irish Times

- ↑ Ahlstrom, Dick. "'Quantum humour' beams back after absence". The Irish Times (英文). 原先內容歸檔喺16 November 2017. 喺2021-12-17搵到.

- ↑ "Nuclear Files: Library: Biographies: Erwin Schrödinger". 原著喺19 February 2023歸檔. 喺14 September 2021搵到.

- ↑ Schrödinger, Are There Quantum Jumps, 1952. http://www.ub.edu/hcub/hfq/sites/default/files/Quantum_Jumps_I.pdf 互聯網檔案館嘅歸檔,歸檔日期11 April 2021.

文獻

編輯- Moore, Walter John (1989). Schrödinger – Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7. 喺23 January 2024搵到.

- Moore, Walter John (1992). Schrödinger – Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7. 喺7 November 2011搵到.

- Moore, Walter John (1994). A Life of Erwin Schrödinger (第Canto版). Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:1994les..book.....M. ISBN 978-0-521-46934-0.

- Gribbin, John (2012). Erwin Schrödinger and the Quantum Revolution. Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4464-6571-4. 喺11 February 2017搵到.